Hey friends!

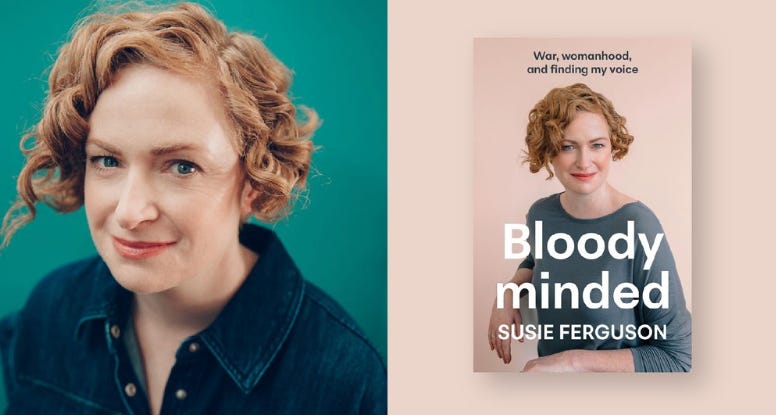

Welcome to the November instalment of Obsessions Monthly, featuring award-winning journalist and broadcaster Susie Ferguson.

In anticipation of our upcoming conversation for Verb Readers and Writers Festival (aka the best writers festival in the land), Susie spoke to me about the part that obsession has played in her life and career, including the writing of her new memoir Bloody Minded: War, Womanhood, and Finding My Voice.

You can join us in Wellington to discuss the book in-depth and in-person at Susie Ferguson: Bloody Minded, Sunday November 10th at Hannah Playhouse, for Verb.

🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️🎙️

When I first asked Susie Ferguson if she wanted to talk about obsessions, she was unsure it would work. Unlike Emily Writes, Susie doesn’t have the kind of niche obsession that makes a great headline. Would we have enough to talk about?

So she asked her husband, Lee: “Do you think I'm obsessive?”

“And he was like, are you joking?!” she laughs, “Everything you do, Susie, you get obsessed.”

From childhood rituals with her Barbie dolls to facing down the darkest aspects of humanity in conflict zones and collecting intimate stories of unimaginable loss, Susie Ferguson’s obsessive attention to detail has always been a driving factor.

She talks with me about all that and more, for Obsessions Monthly.

Susie Ferguson grew up in Edinburgh, Scotland, an only child of two working parents. Her Dad was a family doctor and officer in the Territorial Army, her Mum was an anatomist at the University of Edinburgh Medical school, and the only Mum Susie knew of that worked full time.

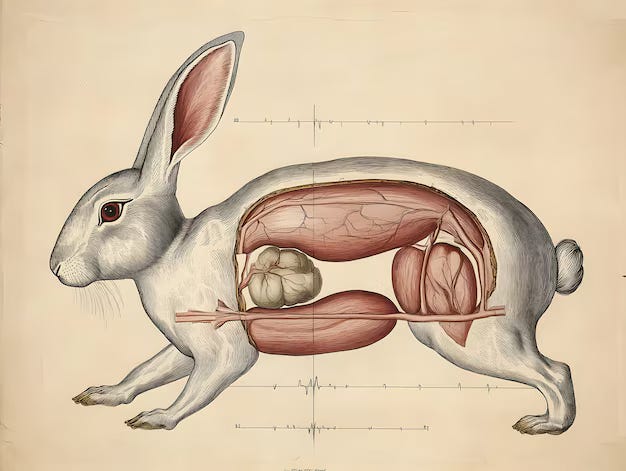

In one particularly memorable scene in Bloody Minded, Susie’s Mum hits a rabbit while driving, and rather than leaving it to scavengers, collects it and chucks it into the boot of the car. Once home, the creature is pinned to a chopping board for an impromptu dissection: Susie watches in wonder as her mother points out the nipples it uses to feed its young, before slicing down its middle and prying open its ribcage to reveal the tiny organs.

To a different child, this kind of event might become committed to memory from a place of horror, but Susie was fascinated. It felt ritualistic, watching the reverence with which her mother worked.

David Fincher, the filmmaker behind Se7en and Fight Club, said: “My idea of professionalism is probably a lot of people's idea of obsessive.” It’s a sentiment Susie can get behind. Reverence, dedication, never settling for less than your best, perhaps even a spot of “bloody-mindedness”: these are the principles Susie carried from her childhood into her working, adult life.

“You have to, I think, enjoy that practice of obsession. Of being consumed by the thing,” she says.

“I don’t know how I would do the job that I do… without that element of being all-in. You just keep going and going and going… And all of a sudden you realise that you’re a long way from where you began. It’s like that meme of the guy standing in front of the board with all the red string going between things… That’s just how my brain works. I think I’ve always been like that.”

🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸

Over her lifetime, Susie has found herself consumed by a handful of major passions, each making their mark on that period of her life before leading her into the next.

An intense child who enjoyed the company of adults more than other children, Susie was known to finish a book and immediately begin to re-read it.

She loved My Little Ponies and Barbie dolls: the latter of which she would attend to every Sunday, shampooing and conditioning their hair before laying them out in front of the gas fire to dry (one day she placed one too close and its face melted and caved in. “Did you keep her?” I ask. “No,” replies Susie wryly, “She was no longer beautiful so I discarded her.”)

After her high school studies were derailed by a nasty bullying incident, Susie turned to a place she had always felt joy: theatre. She attended The Royal Central School of Speech & Drama, graduating with a degree in Drama and Education. But Susie was convinced she’d be a terrible teacher, and had little interest in suffering for her art, the way she saw creative professionals around her doing.

During a chance encounter with a careers advisor, Susie confessed she was a little stuck. “Well, what do you like about theatre?” the woman asked. For Susie, it was the storytelling aspect: weaving the pieces of a narrative together into a compelling whole. She also enjoyed elements of performance, particularly when it came to voice work.

“Well, what about broadcast journalism?” the advisor suggested.

Susie had never even considered it, but all of a sudden it seemed so obvious. She applied to a bunch of postgraduate courses, got in, and the rest - as they say - is history.

Early in her broadcasting career, Susie was thrust into newsrooms and then war zones, where she covered active conflicts including in Iraq and Afghanistan. Both environments proved themselves to be difficult places to be female, but Susie faced it all with her trademark grit: from a threatening run-in with an aggressive editor seconds before she went live on air, to the near-constant sexist and leering “jokes” from the soldiers she lived elbow to elbow with.

During this time, Susie was also battling heavy periods accompanied by debilitating pain, which even 15 pills a day couldn’t quite get on top of. Throughout her book, this pain is ever-present, leaving Susie gasping for breath between news bulletins, or dealing with endless bleeds in the middle of an unfriendly desert, and nevertheless she persists: eventually making her way through the gauntlet of health professionals, ranging from well meaning to incompetent to viciously cruel, to an endometriosis diagnosis and eventual hysterectomy that finally, after decades, takes away her pain (it should be noted this won’t be a fix for everyone suffering with endo, but thankfully it was for Susie).

In 2009, Susie left war reporting behind and emigrated to Aotearoa with her husband Lee and their 6-month old baby. She took on newsroom shifts at RNZ, and in 2012 was hired as a full-time producer for Checkpoint. Two years later, she nabbed the role of co-host for flagship news programme Morning Report.

But while Susie’s extensive experience was obviously enough to land her this prestigious, hard-hitting and public-facing role, it wasn’t enough for some listeners - several of whom seemed hellbent on baiting her into self-doubt.

There was the person on Twitter who became convinced she was lying about having been a war reporter, whom Susie spent far too much time and energy trying to convince before giving up and moving on.

There was also the time when Susie was interviewing then-RNZ political editor Jane Paterson about a trip Gerry Brownlee had taken to Iraq, and a listener text in: “Two women talking about war on Morning Report. Why don't you get back to the kitchen?”

“I remember thinking, I've been a war reporter for six years. [Jane] was enormously experienced… We're actually the two most-qualified people, certainly at RNZ, to be having this conversation. But apparently, because we had vaginas, we had to be in the kitchen! It was just straight-out sexism and misogyny. Absolutely unvarnished,” she tells me.

Having presented shows on RNZ myself, I can testify to how belligerent and misogynistic audience feedback can be, especially towards female hosts, and especially over text message. These days, producers read the text feedback before it gets to Susie, so she can focus on doing her job.

“I haven't read the text machine for five or six years, but from what I hear… it can still be a portal into hell,” she tells me.

In September last year, after veteran broadcaster and Saturday Morning host Kim Hill retired from that role, Susie Ferguson was announced as her replacement (she’s since been joined by co-host Mihingarangi Forbes).

It’s a very different job from Morning Report, a hard-hitting news show where the average interview lasts just a few minutes.

“[With Morning Report] there’s an expectation that… you will read everything and listen to all the podcasts and spend your whole life watching the news and absolutely immersing yourself in it… You have to know everything about everything, with Saturday Morning it’s more like you need to know …”

“A lot about a lot?” I offer.

“Yes!” she laughs, “It’s a difference!”

It’s a difference she’s enjoying, and where she still gets to flex her obsessive muscle: dedicating a lot of time to research, while also being allowed the luxury of time spent with the guests themselves, many of whom have extraordinary stories to share.

“Someone asked me one of those kind of icebreaker-type questions recently, you know, ‘If you could have dinner with anyone in the world, who would it be?’ and I couldn’t answer because usually the people that I could sit and talk to forever are not heralded in that way. They’re just people who have had amazing experiences,” she says.

Like Ken Wylie, a Canadian mountain guide Susie interviewed earlier this year, who was buried in an avalanche that killed half his group, and was eventually rescued by one of his clients.

“I've never talked to anybody about what it's like under the snow when you're buried in an avalanche. He was describing it and I remember saying to him, it sounds really beautiful… Those are the sort of people I want to talk to,” she says.

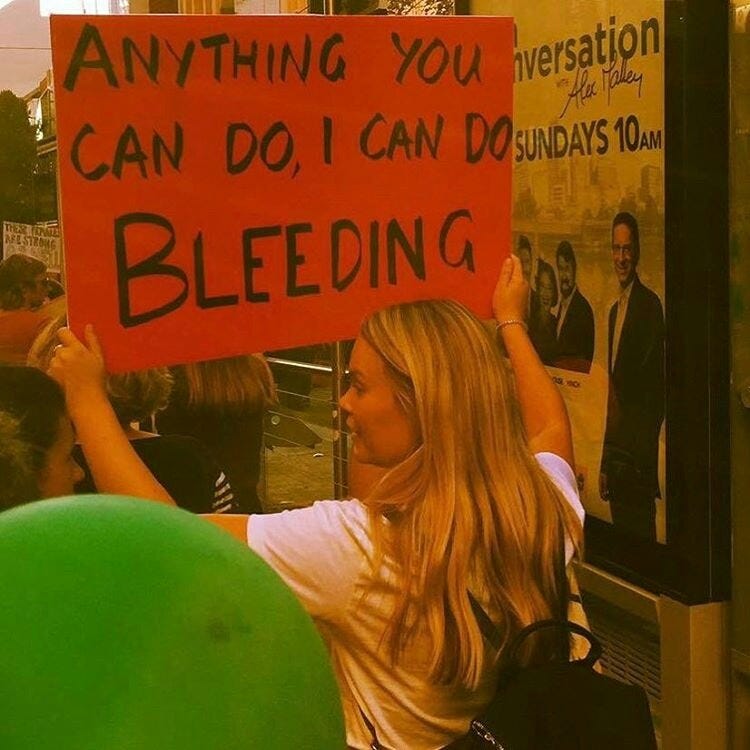

The title for Susie’s book is pitch-perfect: “bloody-minded” as in “very determined and refusing to give up, to change your mind, or to do what others want you to do” (that’s from the Cambridge dictionary online).

But while Susie’s bloody-mindedness has absolutely served her well over her life, she also understands the role of luck.

“There's that great idea that if you work hard, you'll get there in the end. But actually you may work really hard and not get there in the end. There's an awful lot of luck to do with any level of success, and I think anyone who claims that it's all their hard work is bullshitting you,” she says.

The other reason I love Bloody Minded as a title, is because it’s a clever reference to the fact that so much of what Susie has achieved over her life - be it directing a last-minute Edinburgh Fringe Festival show, reporting live from an active war zone, or from the RNZ studio immediately after the Christchurch earthquakes - she has done while literally bleeding.

And to the relief of so many who also suffer pain, stigma and gaslighting over their experience of endometriosis, Susie has refused to keep this fact quiet. When her hysterectomy required her to take 6 weeks off from Morning Report, rather than keeping the reason under wraps as some at RNZ wanted her to do, Susie insisted on telling the truth. She wasn’t ashamed: and why should she be?

“People are so they're terrified of stuff! We've got all these kind of weird Victorian hangover ideas of how [periods are] dirty or unkempt or whatever… But it's a completely normal process. Everyone's been inside a uterus! And I don't understand why people are so weird about a body that half the population have,” she says.

Having spent a good proportion of her life nursing anguish over the relentless agony of endo, as well as the “normal level of self-hatred” most women are made to feel for not being pretty or thin enough (aka “if your face melts too close to the fire, we will throw you away, because you are no longer beautiful”), Susie now finds herself in an unexpected place with regards to her body.

She feels gratitude:

“I just think, fuck it. It's survived so many things. It’s made four pregnancies and it birthed two babies. We should have more self-compassion and be much kinder about that kind of stuff because actually we're fucking amazing. And even without the babies, bodies are amazing. The things they can do and the way that they keep us alive and safe. It's actually mind blowing.”

The final chapter of Bloody Minded is set in yet another doctor’s office, where Susie sits face to face with a young GP she hasn’t met before. She’s been feeling out of sorts. The pain has gone, along with her uterus, but she’s exhausted, increasingly anxious, her joints are creaking and she’s put on an unusual amount of weight. She suspects it’s hormonal, but the doctor is intent on dismissing her concerns, at one point even accusing her of taking up valuable time that might have been given to someone who “actually needed it”.

While she fails to come up with a clever and pithy retort in the moment (she is human after all), Susie does manage to insist she is given blood tests. Soon after, her new GP delivers the news: She’s in perimenopause.

Susie starts on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) patches and within hours feels some kind of return to her old self.

Now that those initial symptoms have passed, Susie feels better than ever. Given the amount of negative, sometimes terrifying anecdotes about menopause, this is a relief to hear.

“There's something enormously peaceful and affirming about [menopause]. I can see why people sort of talk about it being a second life because you're just like, actually, I feel like I've got my shit together, I feel like I know what I'm doing. It feels less mental,” she says.

“Perhaps it will also make me less obsessive, though I suspect that's wishful thinking. I'm still all in, all the time - but maybe a bit less rapid fire!"

Buy Bloody Minded: War, Womanhood and Finding My Voice at a bookstore near you, and come along to hear more about Susie’s life and work as part of Verb Festival on Sunday November 10, tickets at the link below.

See you there!

Melody xx